ANCIENT POST ALARM: Updating my site in September 2025, I find that I wrote this post more than a decade ago, in April 2015. Some of it has aged better than other parts of it. Some of it calls the current-day messaging ecosystems into interesting question... and probably ought make us think a little about, say, microblogging ecosystems these days, too. You can be the judge... just know that it's a decade old.

Starting sometime on April 30th, 2015, you'll find it difficult to contact me through Facebook Messenger. The short story is that Facebook has decided to get rid of the way that I use Facebook Messenger (and, from there, to force me to use their web site); since I try to keep IMs confined to a single window on my desktop to reduce distractions, Facebook Messenger will become completely unusable for me at work, and mostly unusable for me at home. The long story, which you can read below, is that this change reopens the question of Facebook's -- or, really, any company's -- stewardship of how people can interact with their friends, and argues strongly for better regulation of services that have widespread network effects. I have tried to write this article in terms that serve both a technical and non-technical audience.

This post got somewhat more visibility than I'd expected! I've added an update at the bottom with some responses to feedback that I've received. Please feel free to get in touch if you have other feedback, or you can also comment on the Heckler News thread.

Background¶

The first, maybe most obvious, question, is direct. What, exactly, changed, and why does it matter? Facebook have announced that on April 30th, they will be shutting down their chat.facebook.com XMPP server. XMPP (better known as "Jabber", when it's part of an interconnected system) is an instant messaging protocol; you can think of it like a backbone of instant messaging, just as the "Simple Mail Transport Protocol" (a different way that a system of computers talk to each other) is the backbone of e-mail. It's called a protocol because many different systems all act the same way to talk to each other, even if they aren't made by the same company; in fact, even if I didn't have a system that spoke XMPP, it's an "open" protocol, which means that if I were sufficiently motivated, *I// could read about how it works and write a program to make my computer speak with Facebook's.

Luckily, however, I didn't have to, because someone else already had! A bunch of these programs, Instant Messenger "clients", already exist -- and not only can they speak to Facebook, but they can talk to a whole bunch of different instant messaging networks: Internet Relay Chat; the Jabber network at large; AIM (remember that?!); Google Talk (more on that one later...); and a handful more that I didn't list. These programs are useful because they let you put all of your IMs in one place, even if they don't all come from the same network. They also are useful because they let you take control of how you interact with instant messages; for instance, Pidgin (for Windows) and Adium (for Mac) integrate into your desktop like any other app on your computer, and naim integrates into a programmer's "shell". All three of these programs can be extended by their users to add additional functionality, like private and secure messaging (so that the IM service can't read your messages).

I use Pidgin at work, and Adium at home, to connect to Facebook Messenger, because it's important to me that I be able to stay in touch with my friends without the distractions of the rest of Facebook. I'm not the only one; I know at least a few other friends who use Facebook Messenger in this way. Unfortunately, this change will mean that it'll be impossible for me to use Facebook Messenger.

Discussion¶

Obviously, this is very frustrating for me. Facebook has asked me to make a choice in which I can't win: I can either be disconnected from my friends, or I can compromise my ability to perform at work1

This is, of course, not the first time that this sort of thing has happened. Google went almost precisely through this pattern with the Google Talk service (now, Google+ Hangouts). When they introduced it, they advertised heavily that Talk would be interoperable not just with other clients, but with other servers! That meant that, just like e-mail, even if your friend used a service that wasn't owned by Google, you could still communicate with your friend just as well as if they were using Google Talk. Google was so insistent on this being important that they wrote a manifesto of sorts (web archive) discussing why it's so important that users have choice over how they interact with an instant messaging platform. And, of course, when their platform reached a critical mass, they removed some of that choice from their users; now, in order to speak with a Google+ Hangouts user, you have to use Google's servers. (That's slightly less bad than Facebook, though, because for now, you can still use the client of your choice.)

These decisions call into question whether it's appropriate for services that provide "network effects" to operate in a truly free market. User-hostile choices like these, in which a user is forced to use a product, but is railroaded into operating with it on terms other than their own, serve as a form of "invisible middle finger" from the well-known invisible hand. Of course, now is approximately the time at which Facebook apologists reading this article will claim that I didn't pay anything for the service, and how dare I complain about it, and you know man, I can just leave if I don't like it, and hey, what do I expect Facebook to do, just keep maintaining all of their free services for life, huh? And here is the point at which I remind them that they are wrong: I already did pay for the service. I have paid by continuing to use it such that my friends would. I have paid with the currency of my peers. I have paid with my eyeballs, and worse, by selling the eyeballs of my friends to you.

But for all I may be angry at Facebook -- and the people inside that made the choice to exert their power -- the consequences are ultimately mine. When I chose to trust someone else with my data, and to manage my social relationships for me, I gave them the power to screw me over. Jason Scott wrote a classic, albeit somewhat colorful piece2

Conclusions¶

So.

I guess what I'm saying is that you won't see me on Facebook Messenger for much longer, because some people at Facebook decided to abuse my trust. And so, you should think carefully about whether you'll trust them to hold onto your data forever, or whether you've already braced yourself for them taking away a feature that matters to you, too.

Anyway.

See you on SnapChat?

Feedback¶

A few people have mailed me with some feedback, and I wanted to take the opportunity to respond to some of it.

"Well, why don't you just...": I know that this not a fundamentally intractable problem. Why don't you just reverse-engineer the protocol that the mobile app uses? But "why don't you just..." almost always betrays a lack of understanding of what the problem is, and this case isn't any different. My complaint that I can't use the product anymore is one irritation, but even more irritating is that Facebook is moving to an ultimately user-hostile platform. And, even if I focus only on pragmatism, any of the "just" rarely are so simple -- if I had an easy solution, I would probably not bother to write this article at all.

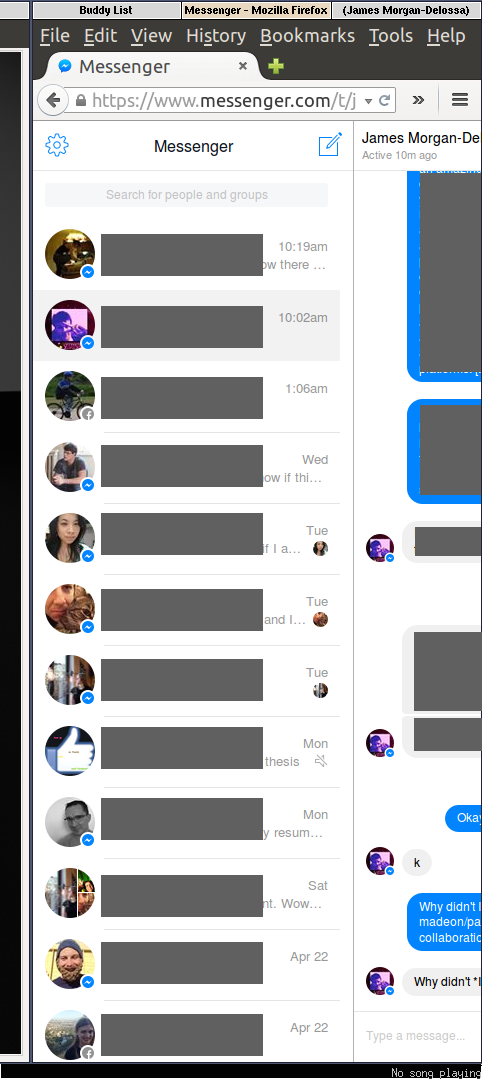

"But seriously, why don't you just use Messenger.com?" Ok, I'll give this one special treatment. In theory, Facebook has provided a desktop client. In practice, it doesn't work for myriad reasons. At right is what it looks like when I fit it into the same space that Pidgin used to fit into at work -- and remember, if I do that, I have to change windows to see my Pidgin buddy list. At home, since Mac OS X activates whole applications at a time, instead of windows, this means that I can't keep a messenger window on top of something else without the rest of my browser taking over, too.3

There are other problems with this that don't just impact me. There are environments in which it's completely unreasonable to sign into Facebook from a web client; for instance, people who work on sensitive things cannot afford to have their Facebook tracking cookie associated with their work. Having Messenger as a webapp means that those users can't use it. And, perhaps more pressingly, having Messenger as a webapp has serious accessibility implications, too: blind, visually-impaired, or otherwise screen-reader-using users will have a substantially degraded experience using Messenger as a webapp. Having a choice of what client to use means that those users can build an experience that works well for them, not just one that was designed for sighted users and shoehorned into fitting them.

I have been aware of Messenger.com, but I didn't mention it because Messenger.com isn't a replacement for XMPP for me: there is no "just use it" about it.

"Surely you don't believe that Facebook are malicious in this?" I don't think it's important whether they were acting with malice, and really, I'm not sure that it's possible to speak of a company as acting with malice or not. Only people can behave that way. It is reasonable to say that the team, however, is acting callously with respect to the users that they have built a trust relationship with. One apt comparison is for a company whose hand is forced; consider the loads of startups that get acquired (or die), leaving their users in a lurch. Facebook differs because they continue to have the social capital that forces users to choose whether to use them under their conditions or disconnect from their friends; when such a startup fails, all of their users disappear at once.

At the end of the day, Facebook's motives don't matter. Their actions alone are enough to call into question whether we should trust them -- or any unregulated service -- to manage our relationships with our friends.

"XMPP is so last century; they were just getting rid of an outdated technology." This one is emphatically not true. XMPP's maintainership is alive and well, and there is new development happening all the time. Kaiwa is a beautiful open-source web client for XMPP, providing similar functionality to Slack. Conversations is an actively-maintained Android client for XMPP, which I use; it has modern-looking design that's on par with any of Google's first-party apps. There are multiple actively-maintained XMPP servers out there, not just a monoculture implementation. And the protocol continues to evolve with "XEPs", which are extensions that bring in modern features like read-receipts and server-side history -- just like Facebook Messenger. XMPP is not dead.

"So how should I contact you?" I've been trying to leave myself out of this to make this article more generally useful. But, the best way to IM me is through Jabber; if you have a XMPP server that supports "choice of server", you can add me as joshua@joshuawise.com. If you use Google Talk or Google Hangouts, then you can add me as joshua.wise@gmail.com (but don't send e-mail there -- I won't receive it). You can send me e-mail always. And, finally, you can still send me messages on Facebook, but I'll be treating it more like e-mail from here on out -- I'll have to check it once or twice a day, and batch up my responses.

-

You might say, "so what? Facebook isn't that bad". For you, that's probably true. For me, that's not true. I've discovered over time that my brain's reward system is wired to be a little more addictive than most. Staring down the "you have n notifications" box is an incentive to take myself away from what I'm supposed to be doing, and read Facebook, which is something that my brain latches onto pretty quickly. I wish that "so what" were the case for me, but it's not. by keeping a Facebook window open (or by checking my cell phone regularly). And, beyond that, there's an ethical issue at play: when Facebook introduced this service, and got early adopters on their messaging platform, they branded their service as a way for users to keep the freedom of choosing what client they like while talking to their network of friends. Once a critical mass of people joined their service, they were free to remove the functionality that got them to where they were, safe in the knowledge that they could not be uprooted. ↩

-

what, you thought I'd make it through this article without linking to that? He also has a piece directly about Facebook that you should totally read. that argues this point; his argument blames ordinary users a little more than I'd like, but I agree with his sentiment: a monoculture that you don't control means always that someone else can do bad things to you, and you should expect it to be coming, really. ↩

-

Yes, yes, I know about Goofy. It'll work right up until the maintainer gets bored with it or Facebook decides to give them the finger, just like everyone else. It's not a solution. ↩