The Coming War on General Computation¶

Presented at 28C3 by Cory Doctorow doctorow@craphound.com.

Transcribed by Joshua Wise joshua@joshuawise.com.

This transcription attempts to be faithful to the original, but disfluencies

have generally been removed (except where they appear to contribute to the

text). Some words may have been mangled by the transcription; feel free to

submit pull requests to correct them!

Times are always marked in #double square brackets.

The original content was licensed under Creative Commons CC-BY

(http://boingboing.net/2011/12/30/transcript-of-my-28c3-keynote.html); this

transcript is more free, as permitted. You may provide me transcript

attribution if you like, or if it does not make sense given the context, you

can simply give Cory Doctorow original author attribution.

The canonical source for this is on GitHub, here.

Christian Wöhrl has submitted a translation of this text into German.

Júlio Garcia has submitted a translation of this text into Portuguese.

Transcript¶

Introducer:

Anyway, I believe I've killed enough time ... so, ladies and gentlemen, a

person who in this crowd needs absolutely no introduction, Cory Doctorow!

[Audience applauds.]

Doctorow:

#27.0 Thank you.

#32.0 So, when I speak in places where the first language of the nation is

not English, there is a disclaimer and an apology, because I'm one of

nature's fast talkers. When I was at the United Nations at the World

Intellectual Property Organization, I was known as the "scourge" of the

simultaneous translation corps; I would stand up and speak, and turn around,

and there would be window after window of translator, and every one of them

would be doing this [Doctorow facepalms]. [Audience laughs] So in advance,

I give you permission when I start talking quickly to do this [Doctorow

makes SOS motion] and I will slow down.

#74.1 So, tonight's talk -- wah, wah, waaah [Doctorow makes 'fail horn'

sound, apparently in response to audience making SOS motion; audience

laughs]] -- tonight's talk is not a copyright talk. I do copyright talks

all the time; questions about culture and creativity are interesting enough,

but to be honest, I'm quite sick of them. If you want to hear freelancer

writers like me bang on about what's happening to the way we earn our

living, by all means, go and find one of the many talks I've done on this

subject on YouTube. But, tonight, I want to talk about something more

important -- I want to talk about general purpose computers.

Because general purpose computers are, in fact, astounding -- so astounding

that our society is still struggling to come to grips with them: to figure

out what they're for, to figure out how to accommodate them, and how to cope

with them. Which, unfortunately, brings me back to copyright.

#133.8 Because the general shape of the copyright wars and the lessons

they can teach us about the upcoming fights over the destiny of the general

purpose computer are important. In the beginning, we had packaged software,

and the attendant industry, and we had sneakernet. So, we had floppy disks

in ziplock bags, or in cardboard boxes, hung on pegs in shops, and sold like

candy bars and magazines. And they were eminently susceptible to

duplication, and so they were duplicated quickly, and widely, and this was

to the great chagrin of people who made and sold software.

#172.6 Enter DRM 0.96. They started to introduce physical defects to the

disks or started to insist on other physical indicia which the software

could check for -- dongles, hidden sectors, challenge/response protocols

that required that you had physical possession of large, unwieldy manuals

that were difficult to copy, and of course these failed, for two reasons.

First, they were commercially unpopular, of course, because they reduced the

usefulness of the software to the legitimate purchasers, while leaving the

people who took the software without paying for it untouched. The

legitimate purchasers resented the non-functionality of their backups, they

hated the loss of scarce ports to the authentication dongles, and they

resented the inconvenience of having to transport large manuals when they

wanted to run their software. And second, these didn't stop pirates, who

found it trivial to patch the software and bypass authentication.

Typically, the way that happened is some expert who had possession of

technology and expertise of equivalent sophistication to the software vendor

itself, would reverse engineer the software and release cracked versions

that quickly became widely circulated. While this kind of expertise and

technology sounded highly specialized, it really wasn't; figuring out what

recalcitrant programs were doing, and routing around the defects in shitty

floppy disk media were both core skills for computer programmers, and were

even more so in the era of fragile floppy disks and the rough-and-ready

early days of software development. Anti-copying strategies only became

more fraught as networks spread; once we had BBSes, online services, USENET

newsgroups, and mailing lists, the expertise of people who figured out how

to defeat these authentication systems could be packaged up in software as

little crack files, or, as the network capacity increased, the cracked disk

images or executables themselves could be spread on their own.

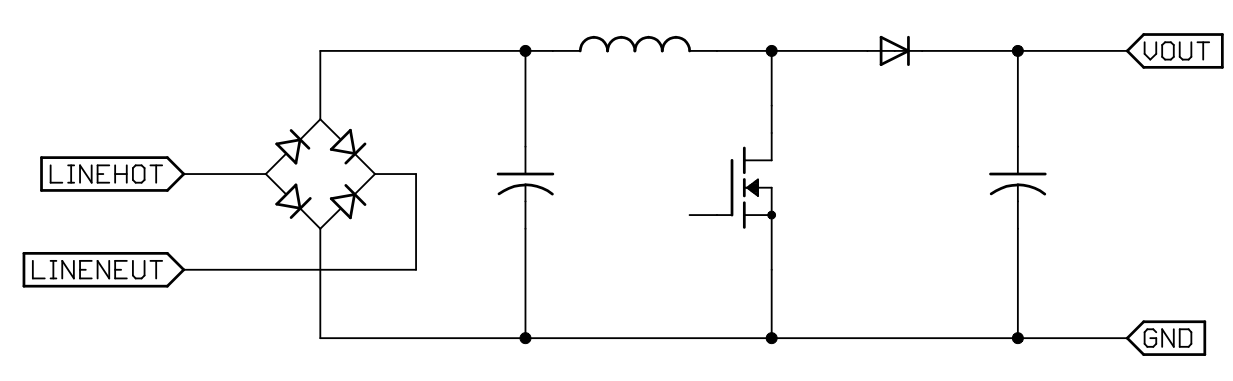

#296.4 Which gave us DRM 1.0. By 1996, it became clear to everyone in

the halls of power that there was something important about to happen. We

were about to have an information economy, whatever the hell that was. They

assumed it meant an economy where we bought and sold information. Now,

information technology makes things efficient, so imagine the markets that

an information economy would have. You could buy a book for a day, you

could sell the right to watch the movie for one Euro, and then you could

rent out the pause button at one penny per second. You could sell movies

for one price in one country, and another price in another, and so on, and

so on; the fantasies of those days were a little like a boring science

fiction adaptation of the Old Testament book of Numbers, a kind of tedious

enumeration of every permutation of things people do with information and

the ways we could charge them for it.

#355.5 But none of this would be possible unless we could control how

people use their computers and the files we transfer to them. After all, it

was well and good to talk about selling someone the 24 hour right to a

video, or the right to move music onto an iPod, but not the right to move

music from the iPod onto another device, but how the Hell could you do that

once you'd given them the file? In order to do that, to make this work, you

needed to figure out how to stop computers from running certain programs and

inspecting certain files and processes. For example, you could encrypt the

file, and then require the user to run a program that only unlocked the file

under certain circumstances.

#395.8 But as they say on the Internet, "now you have two problems". You

also, now, have to stop the user from saving the file while it's in the

clear, and you have to stop the user from figuring out where the unlocking

program stores its keys, because if the user finds the keys, she'll just

decrypt the file and throw away that stupid player app.

#416.6 And now you have three problems [audience laughs], because now you

have to stop the users who figure out how to render the file in the clear

from sharing it with other users, and now you've got four! problems,

because now you have to stop the users who figure out how to extract secrets

from unlocking programs from telling other users how to do it too, and now

you've got five! problems, because now you have to stop users who figure

out how to extract secrets from unlocking programs from telling other users

what the secrets were!

#442.0 That's a lot of problems. But by 1996, we had a solution. We had

the WIPO Copyright Treaty, passed by the United Nations World Intellectual

Property Organization, which created laws that made it illegal to extract

secrets from unlocking programs, and it created laws that made it illegal to

extract media cleartexts from the unlocking programs while they were

running, and it created laws that made it illegal to tell people how to

extract secrets from unlocking programs, and created laws that made it

illegal to host copyrighted works and secrets and all with a handy

streamlined process that let you remove stuff from the Internet without

having to screw around with lawyers, and judges, and all that crap. And

with that, illegal copying ended forever [audience laughs very hard,

applauds], the information economy blossomed into a beautiful flower that

brought prosperity to the whole wide world; as they say on the aircraft

carriers, "Mission Accomplished". [audience laughs]

#511.0 Well, of course that's not how the story ends because pretty much

anyone who understood computers and networks understood that while these

laws would create more problems than they could possibly solve; after all,

these were laws that made it illegal to look inside your computer when it

was running certain programs, they made it illegal to tell people what you

found when you looked inside your computer, they made it easy to censor

material on the internet without having to prove that anything wrong had

happened; in short, they made unrealistic demands on reality and reality did

not oblige them. After all, copying only got easier following the passage

of these laws -- copying will only ever get easier! Here, 2011, this is as

hard as copying will get! Your grandchildren will turn to you around the

Christmas table and say "Tell me again, Grandpa, tell me again, Grandma,

about when it was hard to copy things in 2011, when you couldn't get a drive

the size of your fingernail that could hold every song ever recorded, every

movie ever made, every word ever spoken, every picture ever taken,

everything, and transfer it in such a short period of time you didn't even

notice it was doing it, tell us again when it was so stupidly hard to copy

things back in 2011". And so, reality asserted itself, and everyone had a

good laugh over how funny our misconceptions were when we entered the 21st

century, and then a lasting peace was reached with freedom and prosperity

for all. [audience chuckles]

#593.5 Well, not really. Because, like the nursery rhyme lady who

swallows a spider to catch a fly, and has to swallow a bird to catch the

spider, and a cat to catch the bird, and so on, so must a regulation that

has broad general appeal but is disastrous in its implementation beget a new

regulation aimed at shoring up the failure of the old one. Now, it's

tempting to stop the story here and conclude that the problem is that

lawmakers are either clueless or evil, or possibly evilly clueless, and just

leave it there, which is not a very satisfying place to go, because it's

fundamentally a counsel of despair; it suggests that our problems cannot be

solved for so long as stupidity and evilness are present in the halls of

power, which is to say they will never be solved. But I have another

theory about what's happened.

#644.4 It's not that regulators don't understand information technology,

because it should be possible to be a non-expert and still make a good law!

M.P.s and Congressmen and so on are elected to represent districts and

people, not disciplines and issues. We don't have a Member of Parliament

for biochemistry, and we don't have a Senator from the great state of urban

planning, and we don't have an M.E.P. from child welfare. (But perhaps we

should.) And yet those people who are experts in policy and politics, not

technical disciplines, nevertheless, often do manage to pass good rules that

make sense, and that's because government relies on heuristics -- rules of

thumbs about how to balance expert input from different sides of an issue.

#686.3 But information technology confounds these heuristics -- it kicks

the crap out of them -- in one important way, and this is it. One important

test of whether or not a regulation is fit for a purpose is first, of

course, whether it will work, but second of all, whether or not in the

course of doing its work, it will have lots of effects on everything else.

If I wanted Congress to write, or Parliament to write, or the E.U. to

regulate a wheel, it's unlikely I'd succeed. If I turned up and said "well,

everyone knows that wheels are good and right, but have you noticed that

every single bank robber has four wheels on his car when he drives away from

the bank robbery? Can't we do something about this?", the answer would of

course be "no". Because we don't know how to make a wheel that is still

generally useful for legitimate wheel applications but useless to bad guys.

And we can all see that the general benefits of wheels are so profound that

we'd be foolish to risk them in a foolish errand to stop bank robberies by

changing wheels. Even if there were an /epidemic/ of bank robberies, even

if society were on the verge of collapse thanks to bank robberies, no-one

would think that wheels were the right place to start solving our problems.

#762.0 But. If I were to show up in that same body to say that I had

absolute proof that hands-free phones were making cars dangerous, and I

said, "I would like you to pass a law that says it's illegal to put a

hands-free phone in a car", the regulator might say "Yeah, I'd take your

point, we'd do that". And we might disagree about whether or not this is a

good idea, or whether or not my evidence made sense, but very few of us

would say "well, once you take the hands-free phones out of the car, they

stop being cars". We understand that we can keep cars cars even if we

remove features from them. Cars are special purpose, at least in comparison

to wheels, and all that the addition of a hands-free phone does is add one

more feature to an already-specialized technology. In fact, there's that

heuristic that we can apply here -- special-purpose technologies are

complex. And you can remove features from them without doing fundamental

disfiguring violence to their underlying utility.

#816.5 This rule of thumb serves regulators well, by and large, but it is

rendered null and void by the general-purpose computer and the

general-purpose network -- the PC and the Internet. Because if you think of

computer software as a feature, that is a computer with spreadsheets running

on it has a spreadsheet feature, and one that's running World of Warcraft

has an MMORPG feature, then this heuristic leads you to think that you could

reasonably say, "make me a computer that doesn't run spreadsheets", and that

it would be no more of an attack on computing than "make me a car without a

hands-free phone" is an attack on cars. And if you think of protocols and

sites as features of the network, then saying "fix the Internet so that it

doesn't run BitTorrent", or "fix the Internet so that thepiratebay.org no

longer resolves", then it sounds a lot like "change the sound of busy

signals", or "take that pizzeria on the corner off the phone network", and

not like an attack on the fundamental principles of internetworking.

#870.5 Not realizing that this rule of thumb that works for cars and for

houses and for every other substantial area of technological regulation

fails for the Internet does not make you evil and it does not make you an

ignoramus. It just makes you part of that vast majority of the world for

whom ideas like "Turing complete" and "end-to-end" are meaningless. So, our

regulators go off, and they blithely pass these laws, and they become part

of the reality of our technological world. There are suddenly numbers that

we aren't allowed to write down on the Internet, programs we're not allowed

to publish, and all it takes to make legitimate material disappear from the

Internet is to say "that? That infringes copyright." It fails to attain

the actual goal of the regulation; it doesn't stop people from violating

copyright, but it bears a kind of superficial resemblance to copyright

enforcement -- it satisfies the security syllogism: "something must be done,

I am doing something, something has been done." And thus any failures that

arise can be blamed on the idea that the regulation doesn't go far enough,

rather than the idea that it was flawed from the outset.

#931.2 This kind of superficial resemblance and underlying divergence

happens in other engineering contexts. I've a friend who was once a senior

executive at a big consumer packaged goods company who told me about what

happened when the marketing department told the engineers that they'd

thought up a great idea for detergent: from now on, they were going to make

detergent that made your clothes newer every time you washed them! Well

after the engineers had tried unsuccessfully to convey the concept of

"entropy" to the marketing department [audience laughs], they arrived at

another solution -- "solution" -- they'd develop a detergent that used

enzymes that attacked loose fiber ends, the kind that you get with broken

fibers that make your clothes look old. So every time you washed your

clothes in the detergent, they would look newer. But that was because the

detergent was literally digesting your clothes! Using it would literally

cause your clothes to dissolve in the washing machine! This was the

opposite of making clothes newer; instead, you were artificially aging your

clothes every time you washed them, and as the user, the more you deployed

the "solution", the more drastic your measures had to be to keep your

clothes up to date -- you actually had to go buy new clothes because the old

ones fell apart.

#1012.5 So today we have marketing departments who say things like "we

don't need computers, we need... appliances. Make me a computer that

doesn't run every program, just a program that does this specialized task,

like streaming audio, or routing packets, or playing Xbox games, and make

sure it doesn't run programs that I haven't authorized that might undermine

our profits". And on the surface, this seems like a reasonable idea -- just

a program that does one specialized task -- after all, we can put an

electric motor in a blender, and we can install a motor in a dishwasher, and

we don't worry if it's still possible to run a dishwashing program in a

blender. But that's not what we do when we turn a computer into an

appliance. We're not making a computer that runs only the "appliance" app;

we're making a computer that can run every program, but which uses some

combination of rootkits, spyware, and code-signing to prevent the user from

knowing which processes are running, from installing her own software, and

from terminating processes that she doesn't want. In other words, an

appliance is not a stripped-down computer -- it is a fully functional

computer with spyware on it out of the box.

[audience applauds loudly] Thanks.

#1090.5 Because we don't know how to build the general purpose computer

that is capable of running any program we can compile except for some

program that we don't like, or that we prohibit by law, or that loses us

money. The closest approximation that we have to this is a computer with

spyware -- a computer on which remote parties set policies without the

computer user's knowledge, over the objection of the computer's owner. And

so it is that digital rights management always converges on malware.

#1118.9 There was, of course, this famous incident, a kind of gift to

people who have this hypothesis, in which Sony loaded covert rootkit

installers on 6 million audio CDs, which secretly executed programs that

watched for attempts to read the sound files on CDs, and terminated them,

and which also hid the rootkit's existence by causing the kernel to lie

about which processes were running, and which files were present on the

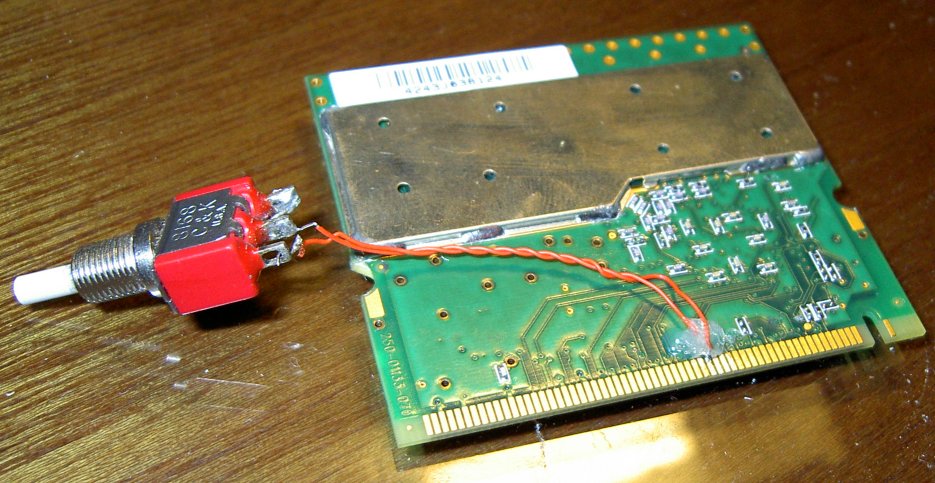

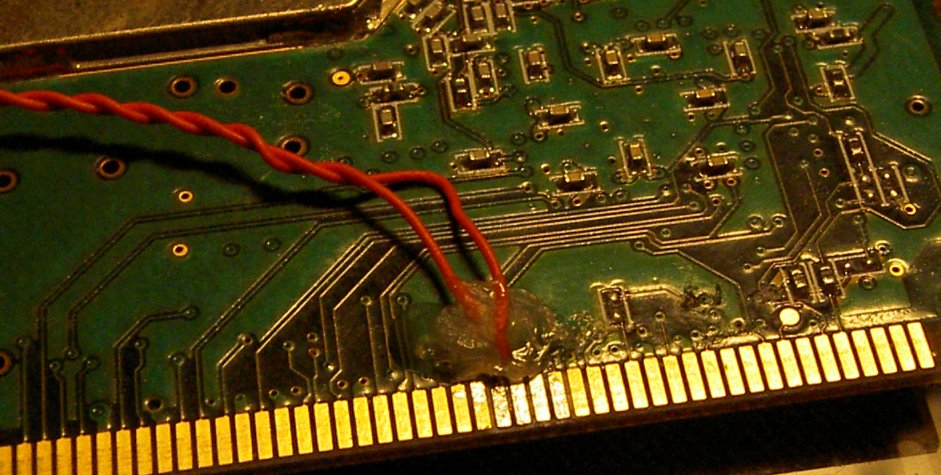

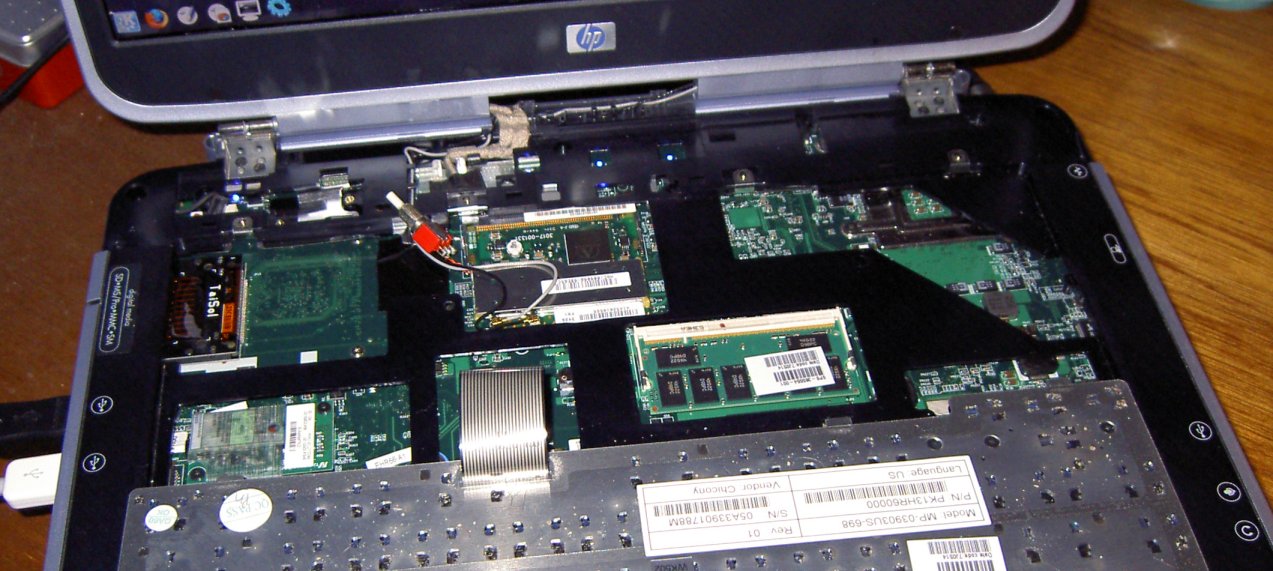

drive. But it's not the only example; just recently, Nintendo shipped the

3DS, which opportunistically updates its firmware, and does an integrity

check to make sure that you haven't altered the old firmware in any way, and

if it detects signs of tampering, it bricks itself.

#1158.8 Human rights activists have raised alarms over U-EFI, the new PC

bootloader, which restricts your computer so it runs signed operating

systems, noting that repressive governments will likely withhold signatures

from OSes unless they have covert surveillance operations.

#1175.5 And on the network side, attempts to make a network that can't be

used for copyright infringement always converges with the surveillance

measures that we know from repressive governments. So, SOPA, the U.S. Stop

Online Piracy Act, bans tools like DNSSec because they can be used to defeat

DNS blocking measures. And it blocks tools like Tor, because they can be

used to circumvent IP blocking measures. In fact, the proponents of SOPA,

the Motion Picture Association of America, circulated a memo, citing

research that SOPA would probably work, because it uses the same measures as

are used in Syria, China, and Uzbekistan, and they argued that these

measures are effective in those countries, and so they would work in

America, too!

[audience laughs and applauds] Don't applaud me, applaud the MPAA!

#1221.5 Now, it may seem like SOPA is the end game in a long fight over

copyright, and the Internet, and it may seem like if we defeat SOPA, we'll

be well on our way to securing the freedom of PCs and networks. But as I

said at the beginning of this talk, this isn't about copyright, because the

copyright wars are just the 0.9 beta version of the long coming war on

computation. The entertainment industry were just the first belligerents in

this coming century-long conflict. We tend to think of them as particularly

successful -- after all, here is SOPA, trembling on the verge of passage,

and breaking the internet on this fundamental level in the name of

preserving Top 40 music, reality TV shows, and Ashton Kutcher movies!

[laughs, scattered applause]

#1270.2 But the reality is, copyright legislation gets as far as it does

precisely because it's not taken seriously, which is why on one hand, Canada

has had Parliament after Parliament introduce one stupid copyright bill

after another, but on the other hand, Parliament after Parliament has failed

to actually vote on the bill. It's why we got SOPA, a bill composed of pure

stupid, pieced together molecule-by-molecule, into a kind of "Stupidite

250", which is normally only found in the heart of newborn star, and it's

why these rushed-through SOPA hearings had to be adjourned midway through

the Christmas break, so that lawmakers could get into a real vicious

nationally-infamous debate over an important issue, unemployment insurance.

It's why the World Intellectual Property Organization is gulled time and again

into enacting crazed, pig-ignorant copyright proposals because when the

nations of the world send their U.N. missions to Geneva, they send water

experts, not copyright experts; they send health experts, not copyright

experts; they send agriculture experts, not copyright experts, because

copyright is just not important to pretty much everyone! [applause]

#1350.3 Canada's Parliament didn't vote on its copyright bills because,

of all the things that Canada needs to do, fixing copyright ranks well below

health emergencies on First Nations reservations, exploiting the oil patch

in Alberta, interceding in sectarian resentments among French- and

English-speakers, solving resources crises in the nation's fisheries, and

thousand other issues! The triviality of copyright tells you that when

other sectors of the economy start to evince concerns about the Internet and

the PC, that copyright will be revealed for a minor skirmish, and not a war.

Why would other sectors nurse grudges against computers? Well, because the

world we live in today is /made/ of computers. We don't have cars anymore,

we have computers we ride in; we don't have airplanes anymore, we have

flying Solaris boxes with a big bucketful of SCADA controllers [laughter]; a

3D printer is not a device, it's a peripheral, and it only works connected

to a computer; a radio is no longer a crystal, it's a general-purpose

computer with a fast ADC and a fast DAC and some software.

#1418.9 The grievances that arose from unauthorized copying are trivial,

when compared to the calls for action that our new computer-embroidered

reality will create. Think of radio for a minute. The entire basis for

radio regulation up until today was based on the idea that the properties of

a radio are fixed at the time of manufacture, and can't be easily altered.

You can't just flip a switch on your baby monitor, and turn it into

something that interferes with air traffic control signals. But powerful

software-defined radios can change from baby monitor to emergency services

dispatcher to air traffic controller just by loading and executing different

software, which is why the first time the American telecoms regulator (the

FCC) considered what would happen when we put SDRs in the field, they asked

for comment on whether it should mandate that all software-defined radios

should be embedded in trusted computing machines. Ultimately, whether every

PC should be locked, so that the programs they run are strictly regulated by

central authorities.

#1477.9 And even this is a shadow of what is to come. After all, this

was the year in which we saw the debut of open sourced shape files for

converting AR-15s to full automatic. This was the year of crowd-funded

open-sourced hardware for gene sequencing. And while 3D printing will give

rise to plenty of trivial complaints, there will be judges in the American

South and Mullahs in Iran who will lose their minds over people in their

jurisdiction printing out sex toys. [guffaw from audience] The trajectory

of 3D printing will most certainly raise real grievances, from solid state

meth labs, to ceramic knives.

#1516.0 And it doesn't take a science fiction writer to understand why

regulators might be nervous about the user-modifiable firmware on

self-driving cars, or limiting interoperability for aviation controllers, or

the kind of thing you could do with bio-scale assemblers and sequencers.

Imagine what will happen the day that Monsanto determines that it's

really... really... important to make sure that computers can't execute

programs that cause specialized peripherals to output organisms that eat

their lunch... literally. Regardless of whether you think these are real

problems or merely hysterical fears, they are nevertheless the province of

lobbies and interest groups that are far more influential than Hollywood and

big content are on their best days, and every one of them will arrive at the

same place -- "can't you just make us a general purpose computer that runs

all the programs, except the ones that scare and anger us? Can't you just

make us an Internet that transmits any message over any protocol between any

two points, unless it upsets us?"

#1576.3 And personally, I can see that there will be programs that run on

general purpose computers and peripherals that will even freak me out. So I

can believe that people who advocate for limiting general purpose computers

will find receptive audience for their positions. But just as we saw with

the copyright wars, banning certain instructions, or protocols, or messages,

will be wholly ineffective as a means of prevention and remedy; and as we

saw in the copyright wars, all attempts at controlling PCs will converge on

rootkits; all attempts at controlling the Internet will converge on

surveillance and censorship, which is why all this stuff matters. Because

we've spent the last 10+ years as a body sending our best players out to

fight what we thought was the final boss at the end of the game, but it

turns out it's just been the mini-boss at the end of the level, and the

stakes are only going to get higher.

#1627.8 As a member of the Walkman generation, I have made peace with the

fact that I will require a hearing aid long before I die, and of course, it

won't be a hearing aid, it will be a computer I put in my body. So when I

get into a car -- a computer I put my body into -- with my hearing aid -- a

computer I put inside my body -- I want to know that these technologies are

not designed to keep secrets from me, and to prevent me from terminating

processes on them that work against my interests. [vigorous applause from

audience] Thank you.

#1669.4 Thank you. So, last year, the Lower Merion School District, in a

middle-class, affluent suburb of Philadelphia found itself in a great deal

of trouble, because it was caught distributing PCs to its students, equipped

with rootkits that allowed for remote covert surveillance through the

computer's camera and network connection. It transpired that they had been

photographing students thousands of times, at home and at school, awake and

asleep, dressed and naked. Meanwhile, the latest generation of lawful

intercept technology can covertly operate cameras, mics, and GPSes on PCs,

tablets, and mobile devices.

#1705.0 Freedom in the future will require us to have the capacity to

monitor our devices and set meaningful policy on them, to examine and

terminate the processes that run on them, to maintain them as honest

servants to our will, and not as traitors and spies working for criminals,

thugs, and control freaks. And we haven't lost yet, but we have to win the

copyright wars to keep the Internet and the PC free and open. Because these

are the materiel in the wars that are to come, we won't be able to fight on

without them. And I know this sounds like a counsel of despair, but as I

said, these are early days. We have been fighting the mini-boss, and that

means that great challenges are yet to come, but like all good level

designers, fate has sent us a soft target to train ourselves on -- we have a

organizations that fight for them -- EFF, Bits of Freedom, EDRi, CCC,

Netzpolitik, La Quadrature du Net, and all the others, who are thankfully,

too numerous to name here -- we may yet win the battle, and secure the

ammunition we'll need for the war.

#1778.9 Thank you.

[sustained applause]